Homegrown folk singer-songwriter Art Fazil has never been one to shy away from experimentation.

His willingness to push himself as an artist, coupled with his passion for Malay music, has resulted in the creation of works that have enriched Singapore's Malay music scene over the last 30 years.

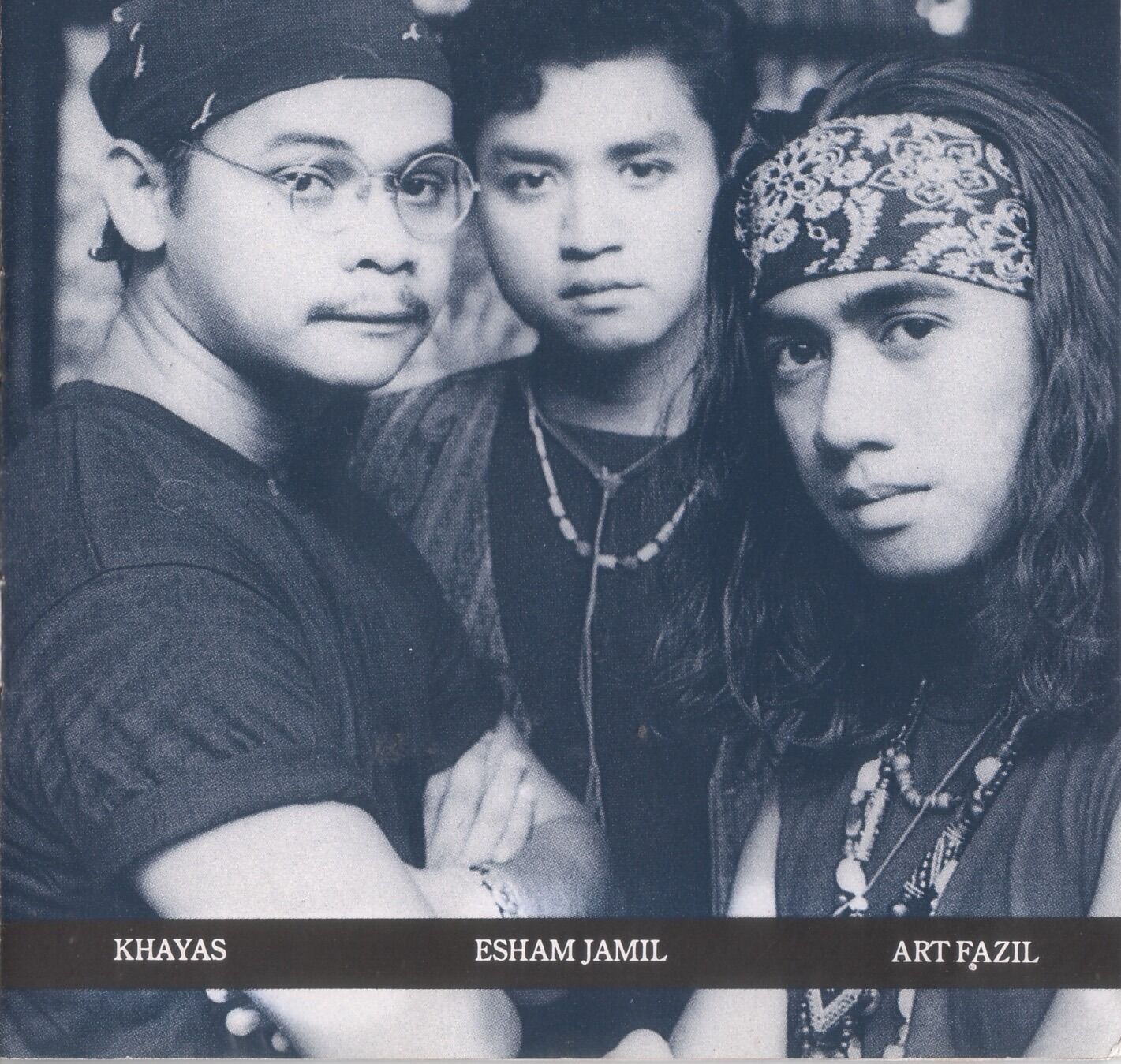

As a member of the folk band Rausyanfikir, Art was — along with the likes of M. Nasir and Ramli Sarip — a champion of the Nusantara music in the early 1990s. This movement, which first took root in the late 1980s, ushered in a golden era for Malay music in which artists created new works by fusing Malay traditional styles with contemporary influences. Inspired by Malay literature, Rausyanfikir also sought to bring themselves and the Malay community closer to their roots through their songs' rich lyrics.

Even as a solo artist, Art remained true to his experimental spirit, adapting and evolving his sound to reach new audiences. During this time, the Anugerah Planet Muzik Award winner also stayed connected to his roots and made a conscious effort to promote Malay culture and music — both locally and internationally — in his creations as well as through exhibitions.

Today, Art continues to be a stalwart of the Malay music community here and an inspiration to artists who are hoping to push the envelope for Singapore's music scene.

"I see Singapore’s Malay music as a soundtrack of a people that are trying to come to terms with cultural changes, urbanisation, displacement, religious revivalism, the loss of native political power, and at the heart of it, sweet love songs to make it through the day."

In the first interview of the In the Spotlight with Hear65 series, Art explores his music's evolution over the years, discusses the importance of Malay music in Singapore, and talks about his efforts to promote his culture.

As a member of the folk band Rausyanfikir, you were one of the champions of Nusantara music in the early 1990s. As a young artist, what drew you to Nusantara music?

I come from a mixed background of various sub-groups within the Malay Archipelago and Indian and Arab via Uttar Pradesh, India. The mix is already in my blood so to speak. Maybe that’s why I am constantly trying to fuse things. I was attracted to the Nusantara style because it is a mix between modern pop and traditional [styles]. P. Ramlee and his peers had done it with the marriage of Latin music such as Rumba, Cha Cha, and even Jazz with Malay melodies. The Nusantara music in the 1990s was very much based on folk, rock, and blues.

I was never trained in Malay traditional music but I have always been drawn to the sound, probably influenced by styles that incorporated traditional Malay and Indian instruments into Malay pop music such as the late Ismail Haron’s eclectic hippie style in the early 70s.

"Nusantara" is an old Sanskrit word that translates to "islands separated by seas" or "Malay Archipelago". In their book "Majulah!: 50 Years of Malay Muslim Community in Singapore", Zainul Abidin bin Rasheed and Norshahril Saat describe the Nusantara movement as "a sense of cultural consciousness". Some topics that Nusantara musicians weaved into their songs included Malay folk stories, spirituality, philosophy, and mythology.

What were you hoping to contribute to the local Malay music scene through your works?

I have always wanted to push the envelope so to speak. I guess we were young and restless. I wanted to make a statement, go against the grain. When I met bandmates Khair Yasin and Esham Jamil, I met my co-conspirators. We became poetic rebels. We started writing songs that were not only thought-provoking but we also wanted to find new musical landscapes to place our poetry. And we were “stealing” sound bites and styles from the existing Nusantara music that was already out there. We just made it into our own style and hoping no one noticed we nicked it from various acts.

"I guess we were young and restless. I wanted to make a statement, go against the grain."

Folk trio Rausyanfikir (Credit: Art Fazil)

Rausyanfikir released its self-titled debut album and Rusuhan Fikiran during this pivotal period, which has been dubbed the “Renaissance of Malay Music”. Where did you draw your inspirations from while working on these albums?

As a band, we were latecomers to the scene, although as songwriters, Khair Yasin and I had been contributing songs to Ramli Sarip. By then we had already been influenced by all the above acts and more. We were also aware of the scene in Indonesia.

Simultaneously, the poetry scenes in Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia were vibrant. Lyrically our influences were the great Malay writers [from these countries]. But sound-wise, I was aware that we had to sound different and contemporary. I was listening to all sorts of music in the late 80s (that was where all my NS allowance went — buying cassettes!) I was into Public Enemy, Tone Loc, and Arrested Development as much as I was into Bob Dylan, U2, and The Beatles.

The first album was rather folky and raw (due to budget constraints). But on the second album Rusuhan Fikiran, we had a bit more money and I wanted to make the music accessible to pop radio. Hence, we got ‘Dhikir Fikir Fikir’ which had a kind of Rap and Rock sound along with some Gamelan sound bites for effect. Songs like ‘Pesta Perut’ had a more African feel with their repetitive riffs.

Rausyanfikir self-funded their two albums as they were unable to land a record deal due to their "non-mainstream stance". Art was also insistent that the group own the rights to the music that they had created.

In what ways were their themes and messages relevant to audiences back then?

Right from the start, Rausyanfikir had a strong built-in social consciousness element. All three of us were writing songs individually with strong social messages. Even Esham Jamil, the crooner of the three of us who was given the task of singing love songs, had written songs that had social messages, such as ‘Orang Kita’. We don’t know if the songs would have an impact or initiate any kind of change but regardless, we just wanted to put them out.

What kind of impact do you think the Nusantara movement has had on the local music scene over the years

The Nusantara movement gave birth to bands like Rausyanfikir, which in turn gave birth to a rap group called Ahli Fikir, which is the literal meaning of Rausyanfikir. Rausyanfikir means “Thinkers” in Persian. We were folk-based and their sound was hip hop, the musical currency of its time. There were other local groups like Nadi and Dinodi and a solo act called Tzi. It also led to an awareness of various acts all over the Malay Archipelago music industry, including Orang Asli (indigenous people) music which Malaysian folk singer-songwriter Dr. Wan Zawawi introduced in his album Dayung. I think the Nusantara movement showed the way that we can make new music by being brave and experimenting with new sounds. [It also reminded us] not to be trapped in a cycle of trying to be the Asian version of a Western act.

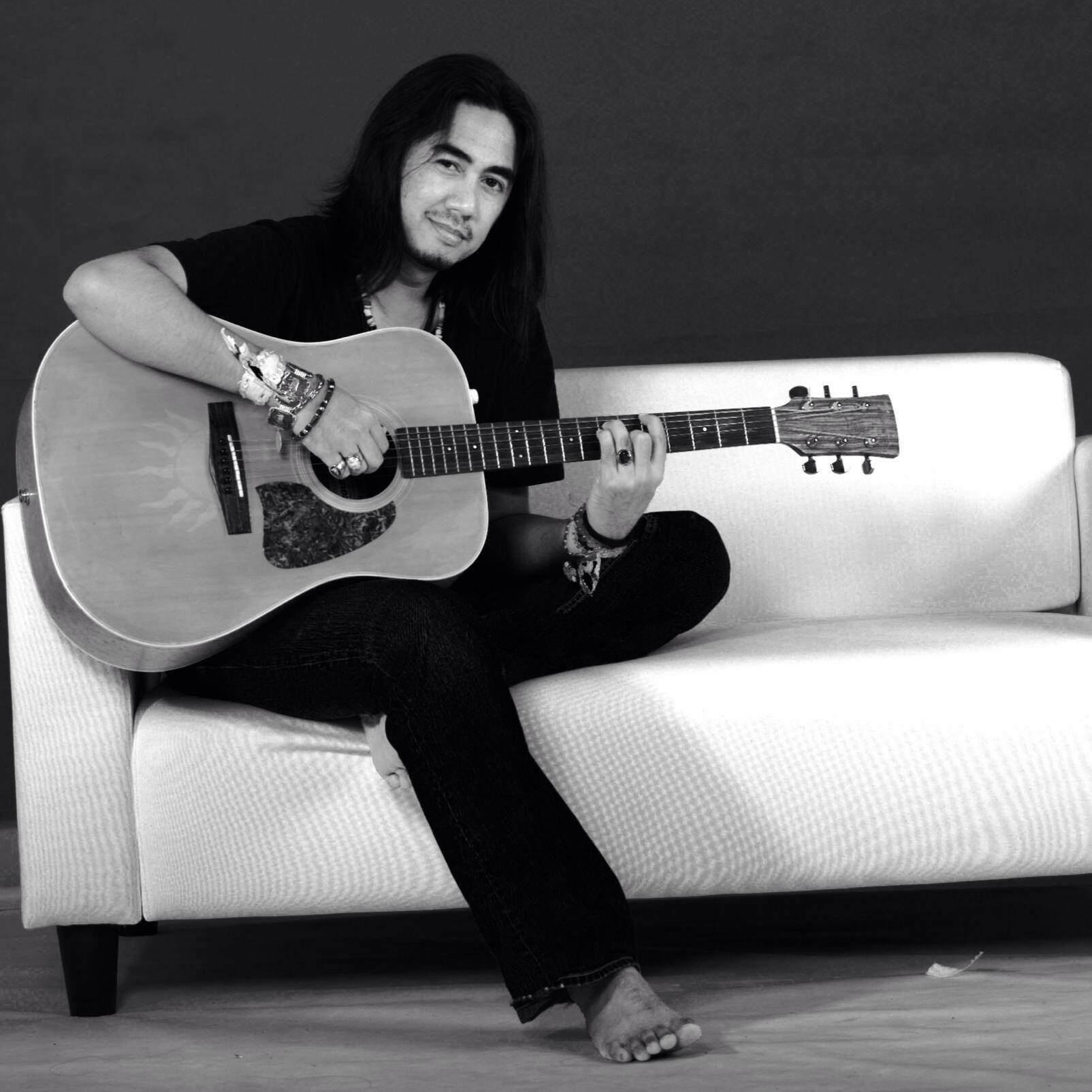

Credit: Art Fazil

Art had written for artists such as Ramli Sarip and Lovehunters and Ella prior to the formation of Rausyanfikir, but 1992 was the year in which his solo career actually began. During his debut show at The Substation, he performed songs that dealt with social issues in Singapore.

Let’s talk about your career as a solo artist. How did you strike a balance between adapting your music to newer audiences and preserving traditions over the years?

I have always considered myself a contemporary artist. I am still working and releasing new works. I cringe at the thought of being a nostalgic 90s act. I try to evolve and sound fresh each time.

"I cringe at the thought of being a nostalgic 90s act. I try to evolve and sound fresh each time."

With my English solo album, it was pop and folk-rock, and with my [Malay] solo album Nur, it was more acoustic pop (some had commented it was like the Malay version of Cat Steven’s 'Tea For The Tillerman’). Then there was Syair Melayu, which was categorised as World Music.

After that, I experimented with something quite different by putting out a single, ‘Rilek Brader’ in 2013 featuring Malaysian artist and comedian, Imuda. It was my first time learning how to program music using Garageband. That song alone had 10 different versions before I decided to release the known version today. It started as a challenge on how to reach out to the Facebook, Twitter, and Youtube generation, so I wrote a simple three-chord song with repetitive lyrics to the point that it annoyed some listeners.

My musical knowledge and performance capabilities are quite limited but I try to work within those limitations and squeeze as much as I can from that.

In 1995, Art moved to London, where he would spend the next 15 years of his career. During this time, he spent three years at The Guildhall School of Music and Drama. He also performed at venues such as the Kashmir Klub, The Rock Garden at Covent Garden, and the Twelve Bar Blues Club.

Did you have to make any adjustments to your performances and music-making process while you were in London? What were the biggest takeaways from your time in the UK?

When I got to London I dived deep into the singer-songwriter stuff. I met some producers and record labels and I showed them my solo English album. They told me what worked in Singapore might not work in London. I got the message and went back to the drawing board, where I relooked at my songs and tried to see how they could work with the London scene. I started playing open mics and trying out new songs, seeing if they would work on the club punters. I even tried busking for a couple of months at the London Underground. That was a life-changing experience and it decidedly got rid of my stage fright. I also made a lot of friends just by playing in public like that. I would seriously recommend any artist that has stage fright to go out busking. It’ll sort you out very quickly.

I also did little festivals around the UK including the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. Looking back, from starting with open mics to a residency performing at a music café in Soho for more than 3 years, it was a great time for me as a musician and as a foreigner in the UK to be part of the scene.

Art performing at the Kashmir Klub in London (Credit: Art Fazil)

In 2009, you reimagined traditional folk songs that you grew up with for your album Syair Melayu (Malay Poems). What inspired you to take on this project?

I had dreamt of the idea of reinterpreting Malay folk songs since I started listening to Nick Drake. That whole folky, soft understatement in presenting the songs. I imagined if the songs were to be represented in visual form, they should be shot with an 8mm camera. [The project] came about as I was researching Malay folk songs online and found cheesy versions made with cheap keyboards and bad programming. I thought the songs deserved a more respectable presentation. In fact, the Syair Melayu album is an adult-oriented album as the melody range is lower than that of children’s songs. It’s sold in Japan as World Music whereas in Singapore, Malaysia, and Indonesia it is sold as children’s songs.

"I imagined if the songs were to be represented in visual form, they should be shot with an 8mm camera."

These are songs that were written hundreds of years ago by unknown songwriters. The Malays did not have written history until much later. Their history is made up of oral traditions passed down from one person to the next, from one village to the next, from poems to poems. And it spreads throughout the [Malay] archipelago that way.

Pre-production of Syair Melayu was done while Art was still based in London. The singer-songwriter recorded the album with the help of traditional music percussionist Qamar Baba after he returned to Singapore. An interesting thing about the project is that it was recorded digitally but mixed on an analogue tape.

In what ways do you think these folk songs are relevant to today’s audiences?

The songs are more relevant now than ever I think because there is a lack of Malay children’s songs in the market. And these classic Malay folk songs have simple melodies and good teaching stories. For example, ‘Bangau O Bangau’ is about the ecology and interconnectedness of life starting with why the egret is so thin right up to the snake eating the frog because that is its food. Two years ago, I took the album on a library tour and performed for young families. It was great to see parents and their young children singing along to the songs. I felt I had accomplished something with the album.

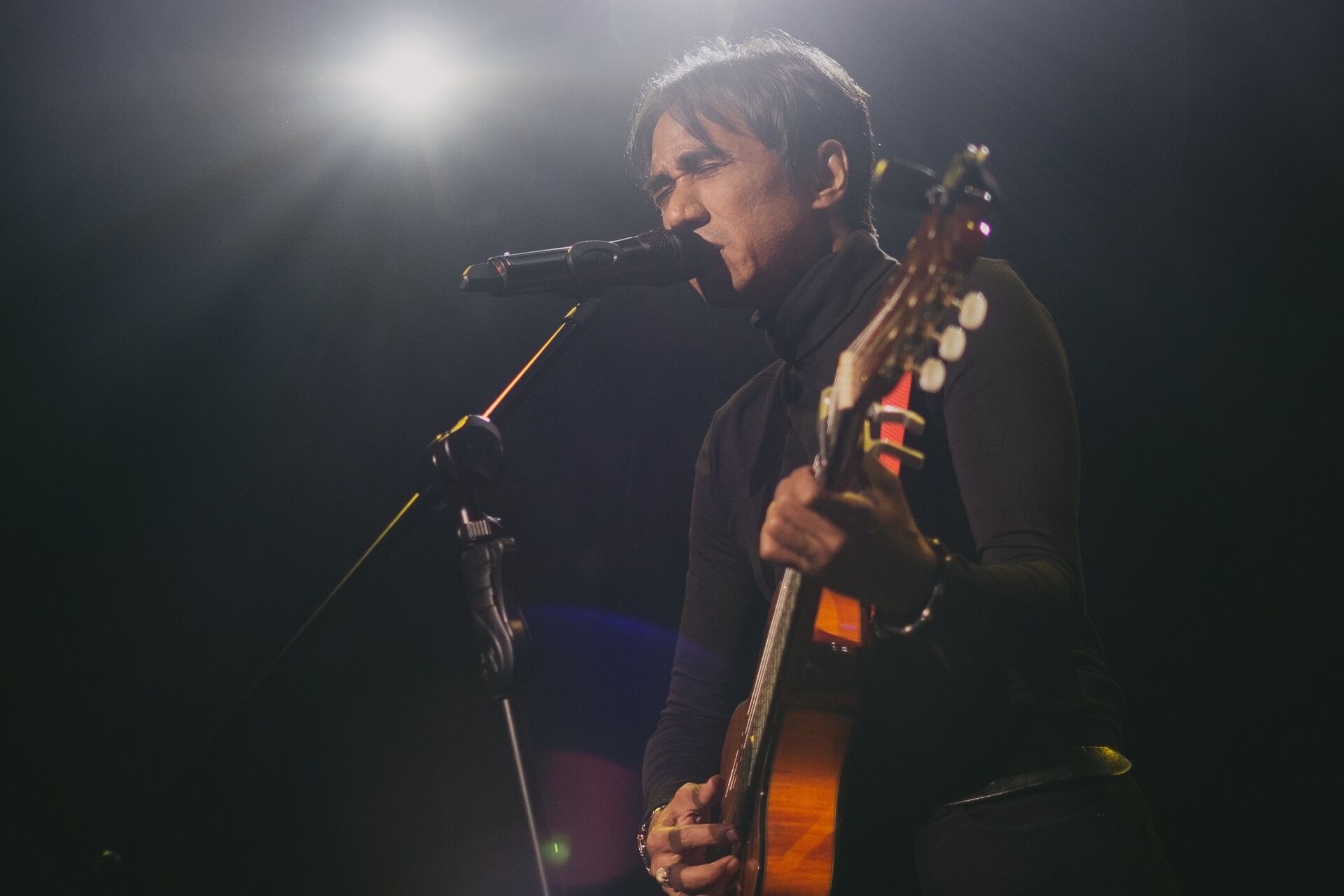

Art at the Kembara@Pustaka concert in 2019 (Credit: Art Fazil)

Stream Syair Melayu here:

What can listeners from outside the Malay community learn about Malay culture and music when they listen to your music?

Malay music has always been syncretic in character since the beginning. Over the years, the styles evolved but some remained unchanged and became “traditional music” like Zapin (which is Arabic) and Ghazal. Even with colonisation, the Malay musicians were not shy to absorb Western musical styles, introduce Western instruments like the violin and accordion, and make a new art form. Keroncong is one example.

More recently, [we had] Rock and Hip Hop. It was the ‘live and let live’, easy-going nature of islanders that was instrumental in the formation of styles by mixing stuff up. And I think it was done rather organically rather than in a studied fashion. It has been said that such is the nature of the Malay people — that we don't go out to conquer distant lands but rather [we take] whatever comes here and make it ours. Music is an example.

Credit: Art Fazil

Driven by his love for his culture, Art organised the first-ever London-Malay festival when he was in the UK. Held in 2005, the event drew the attention of embassies in the UK and was graced by renowned fashion designer Jimmy Choo. Then-Mayor of London Ken Livingstone also showed his support for the festival in the form of a letter.

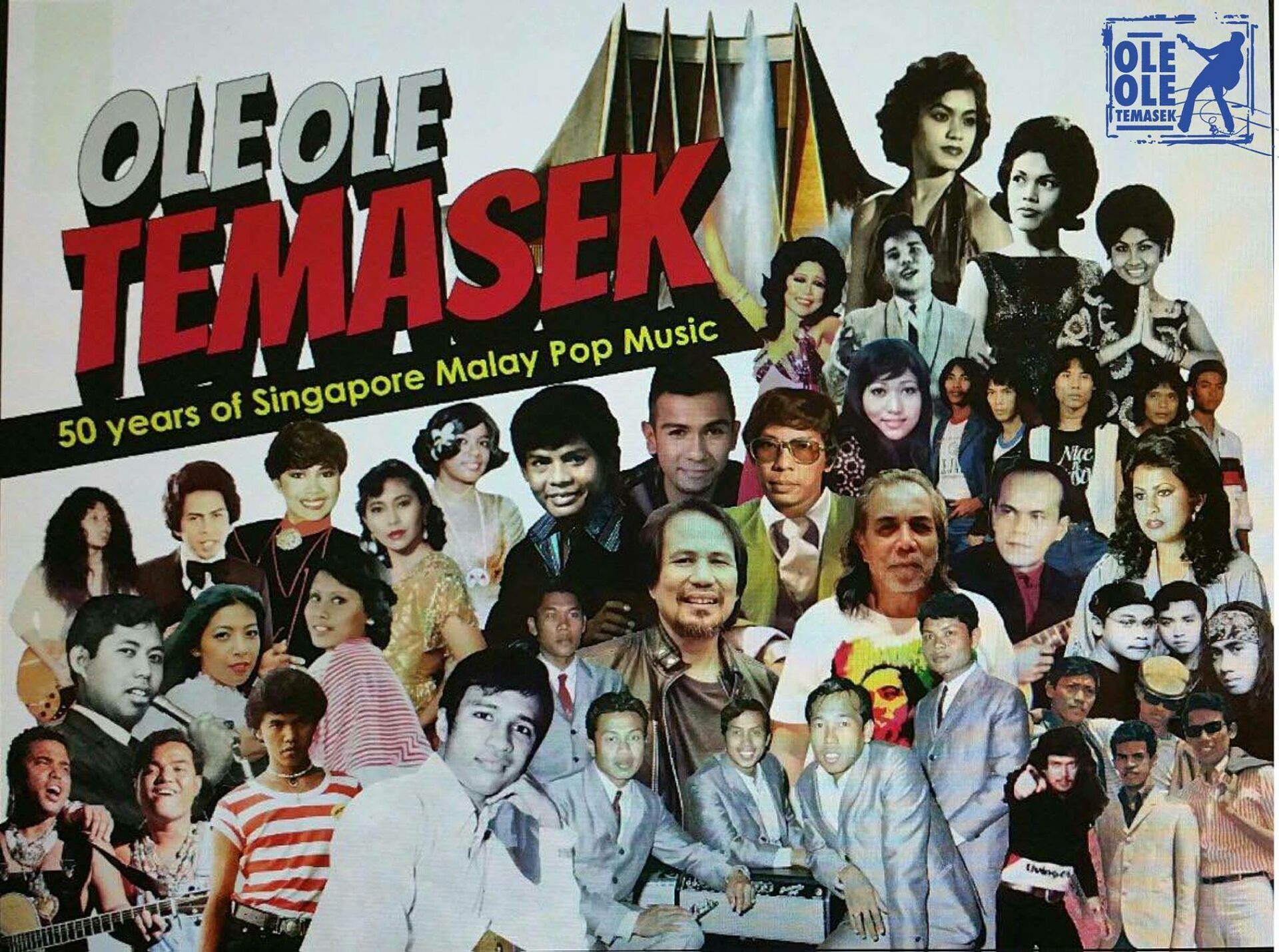

10 years later, Art felt led once more to illuminate the works by the Malay community, this time in Singapore. To do so, he curated an exhibition, named "Ole Ole Temasek: 50 Years of Singapore Malay Pop Music" for the Singapore Heritage Festival.

Tell us more about your efforts to promote Malay music abroad at the London-Malay festival in 2005.

I dreamt up the idea of having a small little festival featuring people from the Malay- speaking world living in London. At first, I thought perhaps [it was going to include] just Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei because I knew people from these countries living in London. Then it got expanded to include Thailand, the Philippines, South Africa, and Madagascar. The idea was to showcase the various expressions of people from very similar base cultures and languages which have expanded and grown over the years with a mix of modernity and colonial influences.

Art performing at IMC Live Global's AL!VE VOL. 1 (Credit: IMC Live Global)

You’ve also helped to promote Malay music locally through the Ole Ole Temasek: 50 Years of Singapore Malay Pop Music exhibition in 2015. How did this project come about?

I saw the opportunity to frame the whole picture of the development of the Malay pop music scene in Singapore with an exhibition that presented the industry since it began in 1965. The idea came about after reading a book called Musika by Azlan Said, which featured works from pre-1965 right down to works from the early 1900s of the Bangsawan theatre culture. [I was also inspired by] the book The Story of Singapore Sixties Music: Apache over Singapore by Joseph C. Pereira.

[The exhibition] was also to show that Singapore had given birth to Malay popular culture, just like the movie industry. It was because we had the latest technology to make music and films and the work opportunities drew talents from around the region. The Malay entertainment crossed over the Causeway in the mid-1980s. And today Kuala Lumpur has replaced Singapore as the Malay popular culture centre.

Credit: Azlan M. Said

What else do you think can be done to keep the flame of Malay music alive?

The competition today is tougher than ever — not just from Western music but K-Pop as well. And there are more distractions for young people these days with online games and social media apps like TikTok. Back in my time, when you were bored you would either watch a movie, read a book, or listen to the radio. Either that or you would write poems and songs. Today, there is little room for boredom and plenty for distraction. Having more music shows on TV and livestream, songwriting contests, and singing competitions definitely would help keep the flame of Malay music alive.

In your opinion, what makes Singapore’s Malay music scene special?

Singapore artists have benefited from the cosmopolitan nature of the island. As the British administration centre, we were exposed to various cultural shifts that were happening in the UK and the world. The ‘Pop Yeh Yeh’ bands of the 1960s were influenced by the British band explosion back then. The local musicians were getting their vinyl records via the British army bases. I have heard that Malaysians would travel to Singapore just to buy a record back in the day. It all started in Singapore.

Without the Singapore Malay music scene, there wouldn’t be a Malaysian music scene today. Walk into Lion Studio vault and you will find miles of recording tapes that make up the bulk of Malay pop music pre-1990 you hear on the radio. A lot of the stuff we hear on Malay radio pre-1990 was recorded in Singapore. Mind you, this music was made against the backdrop of a very real political shift in the country. In a way, I see Singapore’s Malay music as a soundtrack of a people that are trying to come to terms with cultural changes, urbanisation, displacement, religious revivalism, the loss of native political power, and at the heart of it, sweet love songs to make it through the day.

Art performing at IMC Live Global's AL!VE VOL. 1 (Credit: IMC Live Global)

As a veteran in the scene, how do you think you can nurture and guide budding Malay music practitioners in Singapore?

They need to learn about the ecosystem of the music industry — first and foremost how the entertainment business operates, which includes how you monetise your works, royalty collection, performance fees, and all that. Then learn about its history from the international and local industry perspectives, the socio-political landscape, the racism and sexism in the music industry, and the batik curtain of nationalism in some regional markets. [They also need to learn] how to go about beating the system with today’s digital technology.

They need to be aware of the real things, or else they'll be another [batch of] Singaporean artists with an American dream. That is an illusion and like all illusions, it will disappear over time.

Credit: Art Fazil

How do you think Singaporeans can support these musicians and help to develop the local Malay music scene?

It has to start with the promoters, show organisers, and mainstream media. The situation during the COVID-19 pandemic has shown that you need a strong local market. Now, a lot of local show promoters that were used to bringing in foreign acts and ignoring local ones are feeling the pinch. Had we developed a strong homegrown market, they would not have such a big headache now. But it’s never too late. The pandemic is giving us a chance for a restart.

Maybe in the future, we can have a rule where for every foreign artist that performs in Singapore, the promoters should include a Singapore act as the opening act. Make that the practice. I think that can have a good morale-boosting effect.

The mainstream media needs to be revamped and be more proactive. Local Malay radio stations are good at promoting local music but more can be done with TV.

There also need to be programmes that remind people of the past. I tried to do that with my Ole Ole Temasek Exhibition. The Western music industry is good at reminding people of how great their past was through documentaries, books, and magazines. There is always another book about The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Mozart, etc. Without the past there is no today, without today there'll be no future. Today's young musicians probably know more about American pop history than their own.

And perhaps we can start looking into putting more homegrown music at our airports, shopping malls, hotels, and cafes — they all should be made to play music made in Singapore. France has a policy of playing 40% local French music. We don’t ask for 40%, maybe start with 5%.

Stream Art Fazil's discography here: